by Raynner Garcia, BFA Musical Theatre ‘26, School of Theatre and Dance, Columbia College Chicago

On Thursday, June 19, NANIGO 2025 opened in alignment with Juneteenth, a day rooted in both celebration and unfinished justice. For many of us, Juneteenth isn’t just about emancipation, it’s about remembrance. It marks the day in 1865 when enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, were finally informed of their freedom, two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation. While the holiday has now become federally recognized, for Black Americans it has always been sacred. Launching NANIGO on Juneteenth deepened the impact of every moment throughout the weekend.

Just a block from the Dance Center of Columbia College Chicago, the Autin Lo’ren Studio was full of warmth and rhythm the moment we stepped in. You could feel the energy pulsing before any music played; it was a community in motion. As someone with limited experience in Umfundalai, I came with a few nerves, but the generosity of the community quickly washed those away. That is the essence of Umfundalai. More than a technique, t’s a philosophy rooted in Diasporic movement traditions, ancestral connection, and the beauty of the African body. Developed by Dr. Kariamu Welsh, Umfundalai embraces pan-African aesthetics while honoring the spiritual, social, and historical narratives embedded in Black dance.(i)

We began by processing up Michigan Avenue to Grant Park singing, drumming and dancing, drawing in strangers who became temporary kin. Cars were beeping their horns in agreement/asé. By the time we reached the Agora statues, it felt like we had taken up sacred space in a public place, just as our ancestors did, in spirit and resistance. Agbalagba Myrna opened with the pouring of libations, a ritual embedded in African cosmologies from the Yoruba, the Kong, and the Akan. Water, often poured into the earth, honors the ancestors and seeks their blessing. During Juneteenth, the act felt especially weighted; it was for those who resisted, those who survived, and those whose stories never made it into textbooks.

The moment brought me back to my spring production, Piel Canela: Blessed Hands, which I created and produced in collaboration with the Dance Presenting Series. The dance language of Piel Canela is rooted in my heritage: Afro-Dominican and Afro-Cuban folkloric forms. We used movement vocabularies like Palo Congo, Gagá, and Merengue folklorico, all of which descend from spiritual and communal practices brought by Africans enslaved in the Caribbean. Palo Congo, rooted in Kongo religious traditions, channels sacred drumming and trance states.(ii) Gagá, with Haitian roots, is performed during Holy Week in rural bateyes and celebrates spiritual endurance through processional rhythm and dance.(iii) We also drew from Afro-Cuban traditions like Yuka, Makuta, and Orisha dances—techniques grounded in Yoruba and Arará worship that move fluidly between sacred and social spaces. These traditions, like Umfundalai, demand spiritual presence, physical endurance, and deep respect for lineage.

“Every movement was a reminder that we dance with and for each other, not just to perform.”

After the libations ritual in Grant Park, we returned to Austin Lo’ren for a panel with some of Umfundalai’s master teachers: Monique Walker, Dr. C. Kemal Nance, Tabitha Robinson, Sheila Ward, Danzel Thompson-Stout, and Dr. Myrna Amai Clarice Munchus. They reflected on the legacy of Dr. Kariamu Welsh, the creator of Umfundalai, a technique that treats the Black body not as spectacle, but as sacred vessel. Dr. Welsh’s work fused diasporic African Aethetics with contemporary thought, turning dance into both scholarship and liberation. (iv)

We then joined Mama Monique’s class and I’m not sure I’ve ever sweated that much in my life. But her purpose was crystal clear: to cultivate a shared vocabulary rooted in communal energy. Every movement was a reminder that we dance with and for each other, not just to perform.

My experience as a Producer Apprentice for the Dance Presenting Series continues to shape how I think about art-making. From learning technical stagecraft like lighting, audio, and backstage cueing to helping guest artists settle in, these experiences fuel my development as a director and choreographer. On Friday morning of NANIGO, I was honored to escort Agbalagba Myrna to the Dance Center. She opened our day with a Mind, Spirit, and Body workshop, a practice that grounded us through breath-work, intention, and ancestral presence.

Later that day, I returned to a familiar friend, Dunham Technique, taught by Sheila Ward. As someone who studied Dunham as a child, this Level 1 certification class reawakened the roots I first built in elementary and middle school. It reminded me how Dunham, like Umfundalai, centers the spine, pelvis, and polyrhythmic integrity of the Black body. (v)

The Somatics and Anatomy session led by Cheryl Stevens and Ward offered a refreshing, practical perspective. Dancers in African and diasporic forms are often overexerted without proper anatomical awareness. This class broke down ways to protect vulnerable areas like the lower back and feet, something especially important for dancers like me who work in Afro-Dominican and Afro-Cuban forms with heavy percussive footwork.

Then came Danzel Thompson-Stout’s class, a contemporary interpretation of Umfundalai, full of technical rigor and spirit. We opened with the Four Points of the Universe head articulations and moved into Nanigo, dual-circle configurations: one inner, one outer which gave us the opportunity to greet and dance together, creating kinetic synergy that filled the room. The across-the floor sequences, Across the Earth in Umfundalai, were demanding but deeply satisfying.

As I spoke with the elders, I kept hearing the same message: get out of your head and let your spirit lead. I took this with me into Oluko Kemal’s master class, a space reserved for serious practitioners. This was no walk in the park. It started at a 10 and ended somewhere near transcendence. I gave it everything, even when I was out of breath, because I knew this space was earned by me, and by the ancestors who made all this possible.

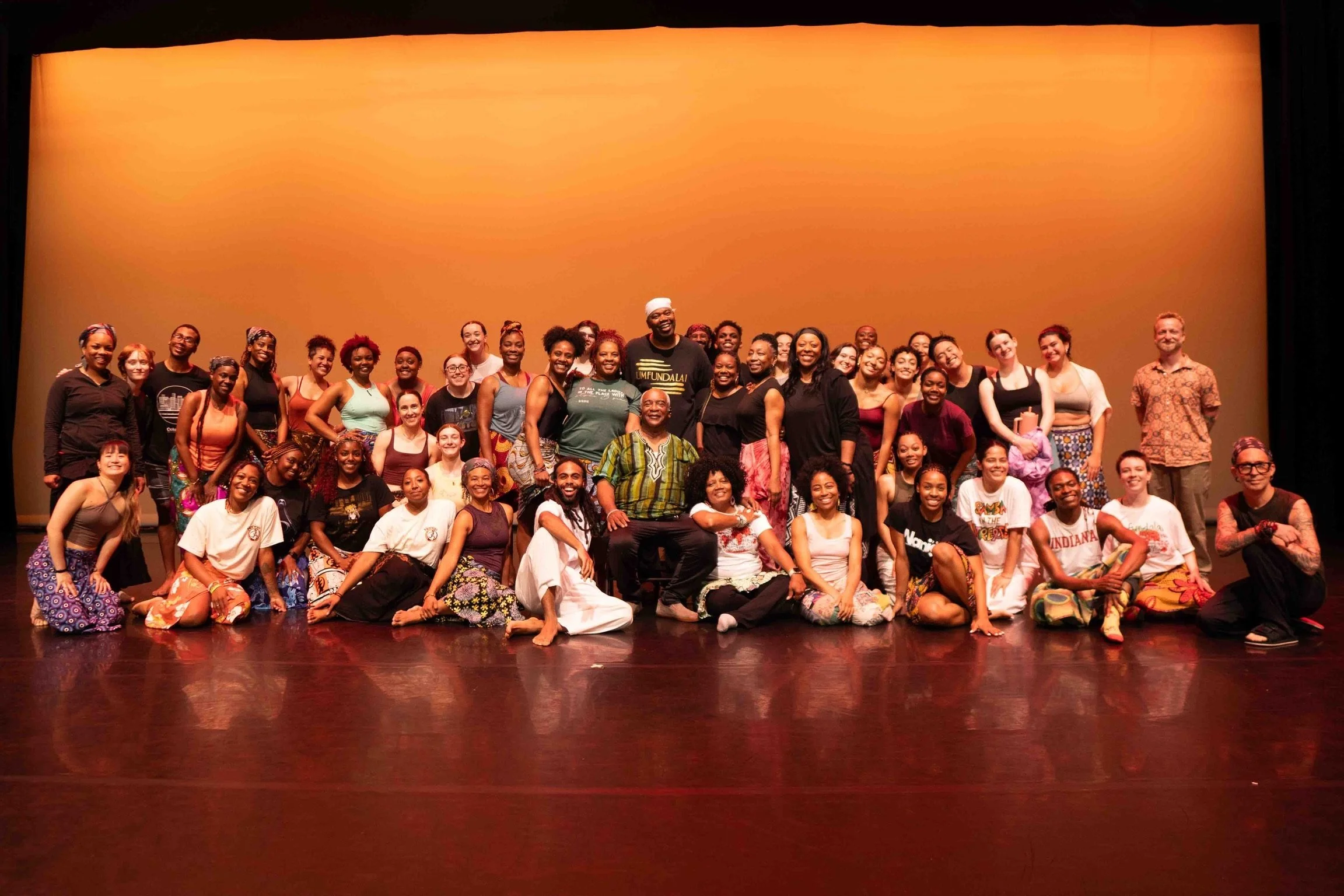

We ended the week with the Dancing Our Africa Showcase, a collection of performances and films that celebrated everything we learned and everything we are still learning. I had the honor of serving as stage manager for the concert, a skill I’m refining more and more. Managing timing, transitions, and atmosphere while holding the emotional pulse of performers is its own kind of choreography.

“This was Juneteenth as it should be observed, not just a celebration, but a return to source, a dance with the past in the service of the future.”

I left NANIGO 2025 exhausted, inspired, and full. This was Juneteenth as it should be observed, not just a celebration, but a return to source, a dance with the past in the service of the future.

Thank you to Professor Bevara Anderson for guiding this conference with care. Huge shout-out to Roell Schmidt, Meredith Sutton, and the Dance Presenting Series for creating space for artists like me to grow. And thank you to the National Association of American African Dance Teachers (NAAADT) for bringing NANGIO to Columbia College Chicago. I’m already looking forward to next year at California State University Long Beach.

Keep following the journey – more movement, more story, more spirit – on instagram @Raynner.g.

Ayibobo. Ashé. Y pa’late siempre.

i. Welsh, Kariamu. The African Aesthetic: Keeper of Traditions. Greenwood Press, 1994.

ii. Thompson, Robert Farris. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy. Vintage, 1984.

iii. Daniel, Yvonne. Dancing Wisdom: Embodied Knowledge in Haitian Vodou, Cuban Yoruba, and Bahian Candomblé. University of Illinois Press, 2005.

iv. Gottschild, Brenda Dixon. Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance. Greenwood, 1996.

v. Dunham, Katherine. Katherine Dunham’s Journey to Accompong. Associated Publishers, 1946.

Banner image by: Aeria Charles (aeriacharles.com)